Everyone in Florida has a different definition of the word native. Ask around, and you’ll meet folks who moved here in 2019 and proudly claim they’ve “been here forever.” Others will tell you they were born in Sarasota Memorial and grew up chasing gators barefoot—making them true locals. But long before any of us were swapping hurricane tips or arguing over the best Publix sub, this land was home to the real Florida natives: Indigenous tribes who lived, ruled, and thrived here for thousands of years. Their footprints are still with us—buried in shell mounds, hidden beneath spring-fed waters, and echoed in the very ways we move through this landscape.

The most powerful and influential of these groups were the Calusa, who dominated the lower Gulf Coast for centuries before and during the arrival of European explorers. But the Calusa were not alone—archaeological evidence also points to the presence of earlier Archaic cultures and the people of the Manasota and Weeden Island traditions. Each of these groups left their mark on the area’s natural and cultural landscape.

One of the most fascinating sites in North Port is Warm Mineral Springs, a deep sinkhole with year-round 85-degree water. It’s not just a spa—it’s one of the most important archaeological sites in the United States. In the 1950s and ‘60s, scientists discovered human remains in the spring’s depths that date back more than 10,000 years. These included preserved bones, wooden tools, and even brain matter, suggesting early burial rituals and a long-standing human presence in the area. The individuals who used this site predated the Calusa, but they laid the foundation for Florida’s Indigenous traditions of water, healing, and ceremony.

The story begins more than 12,000 years ago. At that time, Paleo-Indians roamed the peninsula hunting mastodons and giant ground sloths. As the climate warmed and sea levels rose, these early peoples adapted, establishing semi-permanent camps and gradually shifting from big game hunting to fishing and gathering along the coast. By 4,000 years ago, people had begun to settle in Southwest Florida in more complex, organized ways—leading to the development of shell mound communities that would define the region’s pre-Columbian history.

By around 500 BCE, a culture known as the Manasota people emerged along the Gulf Coast, named after archaeological finds in the Manasota Key area. They lived in small settlements, built burial mounds, and relied heavily on fishing, shellfish gathering, and toolmaking. Over time, their culture merged with or evolved into what’s known as the Glades culture and eventually gave rise to the Calusa.

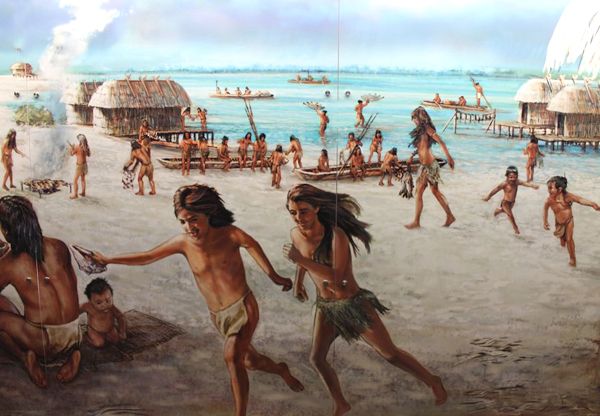

The Calusa were at their height when the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s. Unlike many other Native tribes in the southeastern U.S., the Calusa didn’t farm. Instead, they were full-time fisher-gatherers who created a stratified society supported by skilled engineering and resource control. Their capital was located on Mound Key in Estero Bay, about an hour south of Wellen Park, where they constructed raised ceremonial platforms, watercourts for trapping live fish, and large wooden structures housing hundreds of people.

The Calusa dominated the coast from modern-day Tampa Bay down to the Florida Keys. They were known to control smaller tribes through trade and tribute, using dugout canoes to travel between coastal villages and barrier islands. Spanish explorers estimated that the Calusa kingdom numbered at least 20,000 people. Their society was highly organized, with a ruling chief, a noble class, and a priesthood that oversaw complex rituals tied to the sea and celestial cycles.

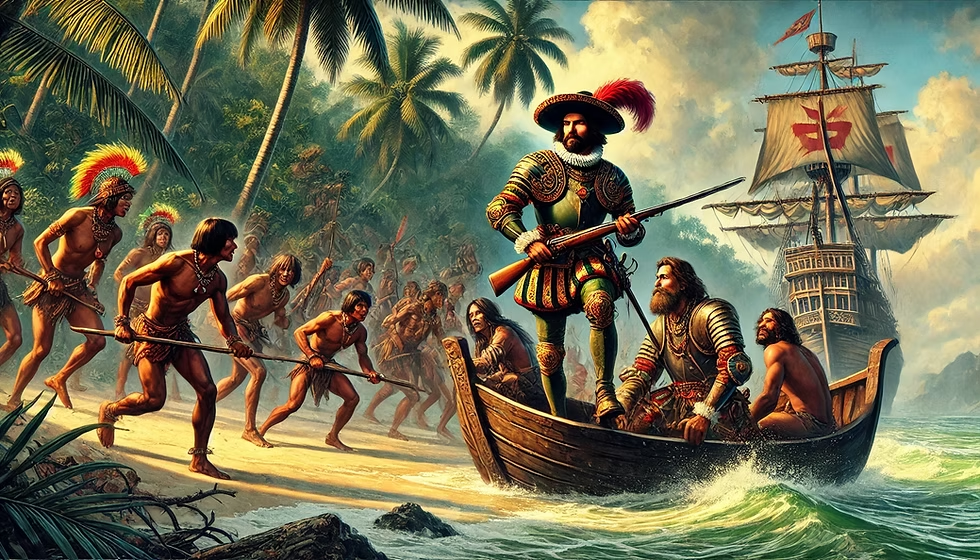

When Juan Ponce de León attempted to establish a colony in Southwest Florida in 1513, the Calusa repelled him with force. His second attempt in 1521 ended with his death after a Calusa attack. Other Spanish efforts to missionize or control the Calusa failed. In 1567, Spanish soldiers and Jesuit priests built Fort San Antón de Carlos on Mound Key, but the Calusa never truly accepted their presence. By 1569, the mission was abandoned, and the Spanish retreated. The Calusa maintained their independence for over 150 years—a rarity among Southeastern tribes.

Eventually, however, their power declined. Disease brought by Europeans, combined with slave raids and environmental pressures, took their toll. By the mid-1700s, the Calusa population had diminished significantly. Survivors are believed to have fled to Cuba or merged with other Native groups. Their last known appearance in colonial records was in the 1760s.

Today, the story of the Calusa and earlier Indigenous peoples is still visible if you know where to look. Shell mounds remain in parts of Charlotte Harbor, the Peace River basin, and even some elevated areas along the Myakka River. These mounds weren’t just trash piles—they were ceremonial, residential, and defensive structures built with purpose and precision. They represent thousands of years of human life along this coast.

The Calusa’s influence also lives on in the region’s relationship with water. Their expertise in tidal rhythms, canal digging, and fish traps was unmatched. Ironically, many of the canals dug by modern developers in North Port echo the waterways that Calusa engineers created long before bulldozers and survey maps.

Understanding this deep history helps us appreciate that the land under our feet isn’t just scenic—it’s sacred. It tells the story of people who thrived here long before Florida had highways or house lots. Their reverence for water, resourcefulness, and resilience continue to inspire.